The Two Cohorts: Who’s Sitting in Front of You?

When it comes to managing meniscus tears, expectations and management shifts depending on who’s sitting across from you.

In general, we’re dealing with two main groups.

The Young and Wobbly

Adolescents to early 30s. Usually sporty. Often explosive movers. Almost always ‘knee incident’ stories that involve a twist, pivot, tackle, or some flavour of high-force trauma. MRIs are more common, earlier, in this cohort.

Meniscus tears matter more with these young folks. These aren’t slow degenerative changes marinating over decades. These are clean, traumatic hits — and if you miss the mark on managing them, you could be lining them up for early-onset osteoarthritis or a joint surface that’ll age like milk, not wine.

The aim here is clear: preserve as much meniscus and articular cartilage as you can. Rehab will need to be longer and smarter. If they go under the knife, they’re more likely to get a meniscus repair.

The Old and Stiff

Ah yes — the 40ish+ crowd. Our weekend warriors. Our Masters comp legends.

These knees have stories. Workload. Life load. Sport load. Maybe too many squats. Maybe none at all. And look — I know calling them old and stiff sounds harsh. But I say it with love, I’m one of them. I go to the Club Meetings (1st Monday of Month at the local Scout Hall).

What matters here is that the rules change. The tissue healing window isn’t the same. The activity goals are often simpler — walk a few Ks, chase a toddler, squat to tie a shoe without grimacing. The risk-benefit ratio of surgery is completely different.

And sure, sometimes there is a real traumatic event — a fall, twist, or dodgy step that flipped the joint into chaos. But again: same label, different plan.

If they end up in theatre, it’s usually for a partial meniscectomy — snipping out the troublemaker.

What do the Academic Boffins Tell Us?

The research is now clear—and has been for years. Here’s but a sprinkle of research pixie dust:

Meng et al. — Meniscus tears show up on MRIs in pain free people. Structure ≠ symptoms [1].

Stensrud, Roos, & Risberg — 12 weeks of exercise improved pain, function, and strength [2].

Kise et al. — In middle-aged patients without radiographic OA, rehab matched surgery for patient outcomes — and beat it for strength gains [3].

Herrlin et al. — Even in 2007, patients with degenerative tears and mild OA did just as well with exercise as with surgery + exercise [4].

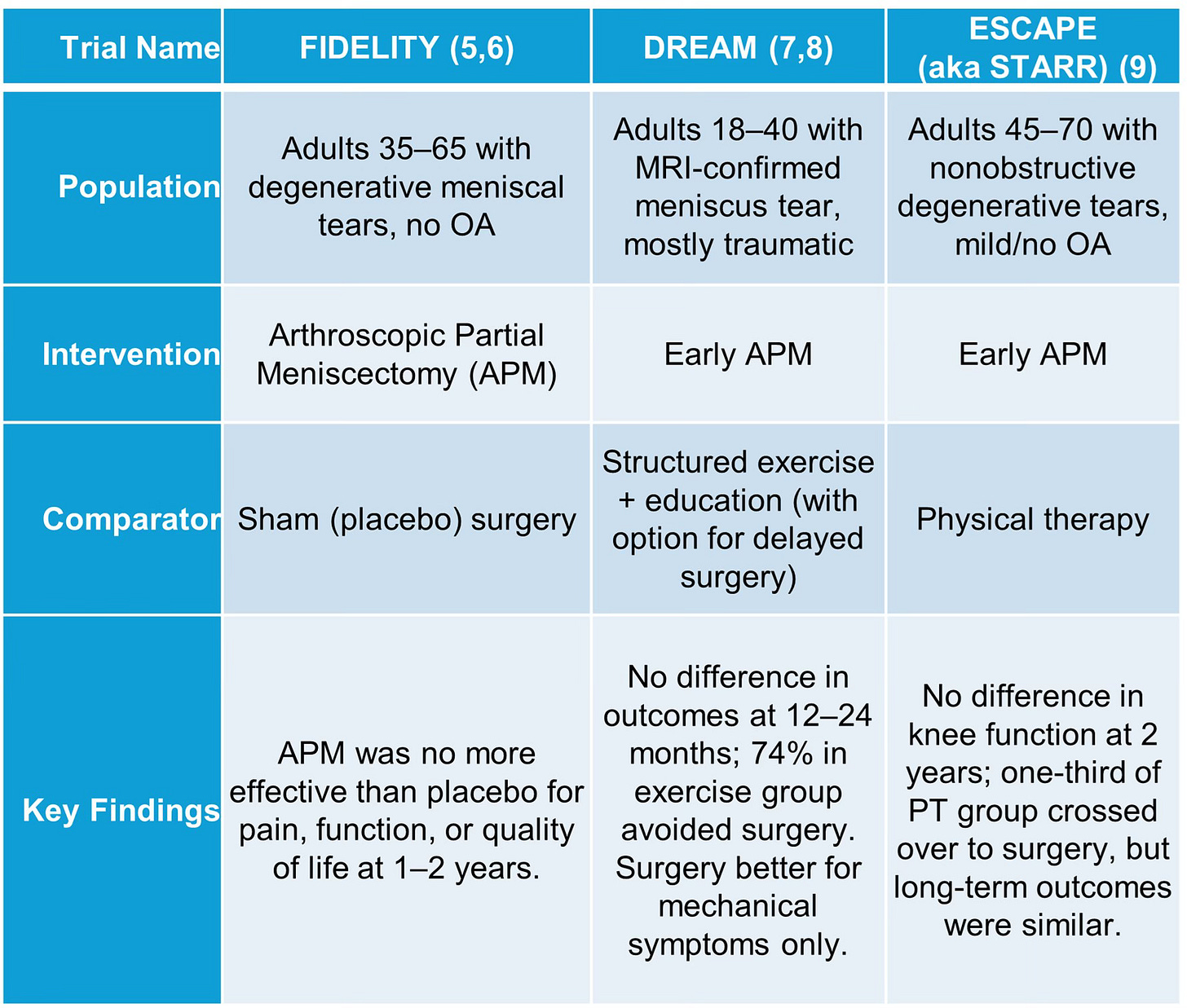

But let’s get to the Big Trials where researchers worked hard to produce high quality acronyms for their titles:

The TRIALs (Targeted Research In Arthroscopy & Loading)

Clinical Application

You’re not ‘delaying the inevitable’ with rehab. You’re giving the joint a legitimate shot at recovery.

Caveat: When the Research Doesn’t Apply

The DREAM and STAR trials showed that supervised rehab often matches surgery — but only in the right knee.

Locked knees, big extension losses, unstable joints, or obvious mechanical symptoms? Those patients were excluded.

Even so, the DREAM trial’s secondary analysis [7] gave us a helpful nugget:

Surgery was better for persistent mechanical symptoms like catching or clicking.

But for pain, function, and quality of life? Rehab held up just as well.

So yes — rehab is powerful. But it’s not magic.

If a knee keeps clunking mid-squat, won’t get past 20° extension, or won’t calm down after 6–12 weeks of proper rehab — that’s not a rehab fail. That’s your sign to escalate.

But what are we looking for exactly?

We’re on the Hunt for ‘Whoopsies’

That’s my technical term for ‘uh-oh’ knee moments:

Locking – “It clunked and now it’s stuck.”

Giving way – “I was walking and it gave out.”

Effusion – “It keeps blowing up.”

A Whoopsie here or there? Fine. But they start to matter more when:

They keep happening

They happen easier

They happen more often

Recovery takes longer each time each time they do happen

That’s when we move from watchful waiting to decisive action. Because while patients might be fine hobbling in at 30° flexion like a pirate yelling “YARGH!” — you know better.

Special Mention: Meniscus ‘Special Tests’I don’t do them. Why would you? Why would you risk stirring it up unnecessarily?

Monitoring for Whoopsies is all we need, right? (nod your head now)…Glad you agree.

Save the special tests for the Orthopaedic Surgeons who have plenty of insurance if things go wrong.

Calm the Knee - Lock it up!

You don’t chase flexion when the joint’s in meltdown mode. First, you calm the chaos.

One of the best tools for this is a hinged ROM (range of motion) knee brace — and no, we’re not talking about slapping on a neoprene sleeve and hoping for the best.

Here’s how it works:

You lock the knee into its ‘happy range’ — usually around 10° short of where the symptoms start in both directions (flexion and extension). If they can move pain free between 10° and 60°, that’s where the brace gets set.

It’s not about pushing boundaries, it’s about building trust — show the knee it’s safe inside this range.

While braced, they can still do basic strength work — even if it’s just isometrics for quads and hams, or some gentle ROM drills, all within that safe zone. Each week, if the knee’s playing nice, you unlock a little more. Not because Week 3 on the ‘Dr Smith Protocol’ says “go to 90°” — but because the joint says, “Hey, I’m ready.”

Once full passive and active knee extension is back we greenlight some walking, and by ‘walking’, we mean just that. Not walk-the-dog-then-hit-up-the-shops-then-school-pick-up kind of walking.Nope: Structured. Limited. Progressively loaded.

Why keep the brace on, even when ROM’s improving?

Yes it’s a structural support, but sometimes it’s a behavioural modifier.

Think: a 17-year-old at school, surrounded by unpredictable human dodgeballs. That brace is a visible signpost: ‘Stay away from this knee’.

And for some? That visual cue alone might protect them more than the actual hinges.

A few extra weeks of bracing might be exactly what they need. Physically. Psychologically. Or just to survive break time.

We don’t unlock and wean from the brace by the clock — we progress by the criteria.

Build Load Capacity Gradually

Start where the joint is at, de-escalate if it’s cranky. Those of us with 2-3 year olds will know this phase well. Give it some quiet time.

Respect irritability, monitor response, and work within the happy zone.

Get started with glutes, quads, hams, calves, any pain free ROM – in the brace.

Track Objectively

It’s not just about pain. It’s about capacity. What can the knee do?

We’re assessing how happy the knee is:

To work – Max* Isometric Knee Extension (KE) Peak Force on Dynamometry

To do quick work – KE Rate of Force Development (RFD) on Dynamometry

To up up/down – Squats on a Force Plates/Decks (Plates)

To go up/down quickly – Countermovement Jump (CMJ) on Plates

To go up/down quickly on THAT leg – Countermovement Hop on Plates

* By ‘max’, what I really ask of the patient is: “I’d like you to push as hard as the knee is happy to push – listen to it, don’t push through pain”.

Criteria/Benchmarks

I’m going to share some of my own Criteria with you – perhaps the ‘median’ of conservative rehab criteria I’ve focused on over the past decade or so once dynamometry became more commonplace.

Full, pain free extension A must. All knee rehab.

60% pain free knee extension force production LSI (Limb Symmetry Index (LSI))Start walking more.

110° pain free flexion – progressing to full pain free flexion.

Or enough flexion to start cycling at low-intensity with full revolutions.

80% pain free knee extension force production LSI Walk-jog progression starts here.

80% pain free RFD (vs. unaffected side)Start increasing deceleration and change of direction demands, already commenced earlier. Start gradual exposure to sport/exercise.

<10% LSI in force production LSI and RFD LSIHigher demand loading and return to competitive sport/exercise.

And those are just for the older and less athletic. For the younger and athletic, there’s many more criteria needed towards mid-late stage rehabilitation.

These are just an example, they aren’t set in stone, they differ from case to case. Please don’t make them ‘Dr Ilic’s Protocol’. Disclaimer: I am not a doctor. This is not a protocol.

Case Study: From ‘Failed Rehab’ to Full Recovery

A Meniscus Case Study in Calm, Clarity, and Clinical Reassurance

The Background

A very active and otherwise fit 40ish year old presented for a second opinion three weeks after injuring their right knee during sparring in their combat sport.

The mechanism? An awkward one. They were on the ground with a flexed knee and their opponent landed, full bodyweight, onto their knee. No immediate pain, but they heard and felt a sickening crack. Later that evening, the knee felt ‘gross’, unstable, and nauseating.

The MRI, the Labels, and the Panic

Their GP ordered an MRI, which reported:

A ‘probable’ Grade II MCL tear

A horizontal tear of the lateral meniscus

A smaller tear in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus

A whirlwind of appointments followed: a well-adjusted chiropractor, then a well-meaning physio. No structured plan. Plenty of confusion.

There was no bracing - even for the MCL – which spoke volumes of the standard of care.

They were told they had “failed rehab”. When in doubt: blame the patient.

By the time they saw me for a second (or fifth) opinion, they were booked for surgery the very next day - putting me in quite the professional-pickle.

The knee was irritable, yes, but not unstable. Valgus stress testing of the MCL was tolerable, and the meniscus didn’t present symptomatically.

Based on clinical presentation, there were clear signs that surgery could be avoided at this stage.

To their credit, the surgeon was more than happy to postpone — based entirely on that assessment, and a grovelling letter and email from me.

Calm the Knee, Calm the Person

Rather than rushing into treatment, the first step was reassurance, lots of it.

This patient needed it, they were stressed, they didn’t want surgery, they felt rushed into it. And they had been told lots of nasty things about their knee and progress, or lack thereof.

Initial appointment:

Hinged ROM brace locked to 45–60 degrees gave both the knee — and the patient — a sense of safety

Walking was restricted to necessary steps only, until extension returned

The brace gradually unlocked as ROM improved, matching the knee’s progress

Summary of Bracing meeting Criteria:

Progress was steady and personalised.

Knee Happiness + Dynamometry dictated the next step: not time.

They returned to light combat sport training at 12 weeks, gradually dialling up over 102 months and were discharged from rehab at 18 weeks — confident, strong, and independent.

Clinical Reflection

This wasn’t a miracle case. It was a missed opportunity, rescued by context and calm.

The initial rehab wasn’t wrong — it just didn’t offer what the knee needed: safety, structure, and clarity.

References

1. Meng D, O’Sullivan K, Darlow B, O’Sullivan PB, Ekås GR, Forster BB. MRI for degenerative meniscal lesions: cease and desist! A three-step action plan. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine; 2019. p. 1139-40.

2. Stensrud S, Roos EM, Risberg MA. A 12-week exercise therapy program in middle-aged patients with degenerative meniscus tears: a case series with 1-year follow-up. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2012;42(11):919-31.

3. Kise NJ, Risberg MA, Stensrud S, Ranstam J, Engebretsen L, Roos EM. Exercise therapy versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear in middle aged patients: randomised controlled trial with two year follow-up. bmj. 2016;354.

4. Herrlin S, Hållander M, Wange P, Weidenhielm L, Werner S. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2007;15:393-401.

5. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus placebo surgery for a degenerative meniscus tear: a 2-year follow-up of the randomised controlled trial. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2018;77(2):188-95.

6. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(26):2515-24.

7. Damsted C, Skou ST, Hölmich P, Lind M, Varnum C, Jensen HP, et al. Early surgery versus exercise therapy and patient education for traumatic and nontraumatic meniscal tears in young adults—an exploratory analysis from the DREAM trial. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2024;54(5):340-9.

8. Skou ST, Hölmich P, Lind M, Jensen HP, Jensen C, Garval M, et al. Early surgery or exercise and education for meniscal tears in young adults. NEJM evidence. 2022;1(2):EVIDoa2100038.

9. Van De Graaf VA, Noorduyn JC, Willigenburg NW, Butter IK, De Gast A, Mol BW, et al. Effect of early surgery vs physical therapy on knee function among patients with nonobstructive meniscal tears: the ESCAPE randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2018;320(13):1328-37.